Jon Kaletka

By Jon Kaletka

There are countless apps to keep in touch with friends and family throughout the world.

But have you ever wondered how your body’s trillions of individual cells talk to each other?

That’s what I study to improve the diagnosis and treatment of bacterial infections.

An emerging field of cellular communication is the way tiny particles secreted by cells carry messages to other cells.

Similar to how we use mail to stay in touch, these particles – called extracellular vesicles – deliver messages to the other cells and change what they do. They are implicated in normal cellular functions and in a wide range of diseases. For example, vesicles from tumors prevent the response to diseased cells, allowing the cancer to grow and spread. Extracellular vesicles provide a new way of understanding various diseases and could lead to different ways of treating them.

I study the role of extracellular vesicles during infection caused by Listeria. If this bacterial pathogen sounds familiar, you likely saw it in the news about an outbreak of infections or heard of a recall of contaminated food because of it.

One of the most interesting things about Listeria is that it can live inside our cells, even ones

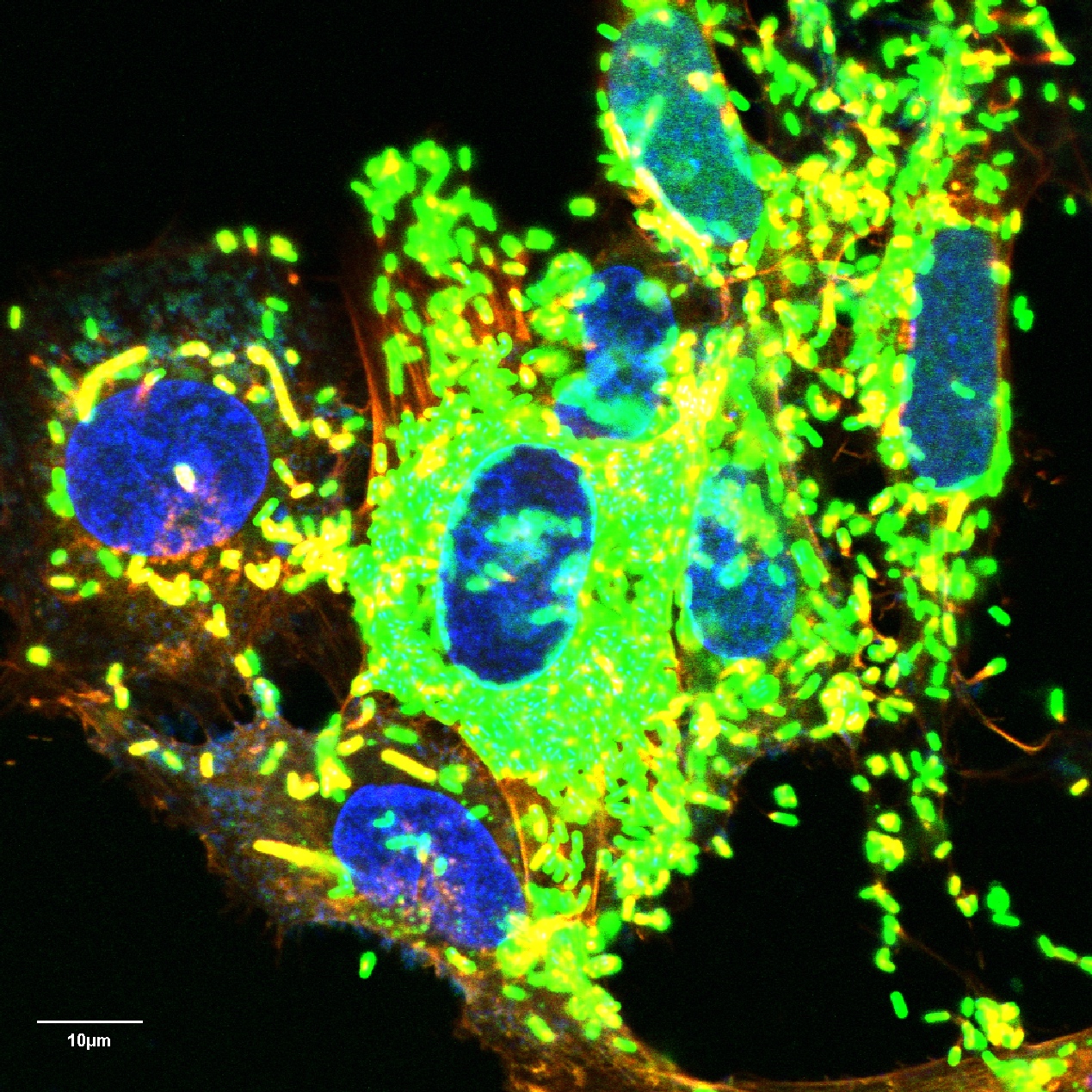

The green and yellow areas are Listeria infecting human cells. The blue are cell nuclei. Image: Melinda Frame and Jon Kaletka

that normally kill bacteria. Think of a jailhouse as an immune cell that contains the bad guys. When the criminal escapes custody, he starts destroying the jailhouse, making it useless. Then he moves on to other buildings, leading to chaos across the city.

This is how Listeria attacks a body – by invading, destroying, and spreading through cells. Our cells need to organize a proper response to combat this invasion. I predict that a way to do that is to use extracellular vesicles.

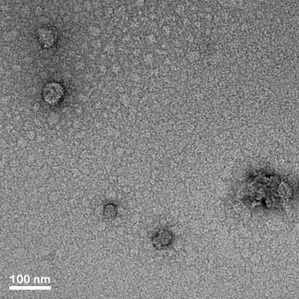

The large objects are extracellular vesicles that carry messages between cells. Image: Alicia Withrow and Jon Kaletka

I have discovered that vesicles from infected cells can activate cells from the immune system, making them more dangerous to Listeria. I have also found that Listeria reduces the number of vesicles infected cells release. This suggest that Listeria could be stopping vesicle production to stave off the body’s defense.

It’s like the escaped criminal cutting off communications going out of the building, preventing calls for help. Delaying this response will help the criminal stay free and cause more damage.

My next challenges are to find out what exactly is being carried by the vesicles and fully understanding how cells respond to the messages.

These findings can lead to new ways to identify and treat bacterial infections.

Jon Kaletka is a doctoral candidate at Michigan State University in the Department of Microbiology and Molecular Genetics. He produced this story during a science communication workshop taught by the Knight Center for Environmental Journalism.